|

|

|

|

November 14, 2005

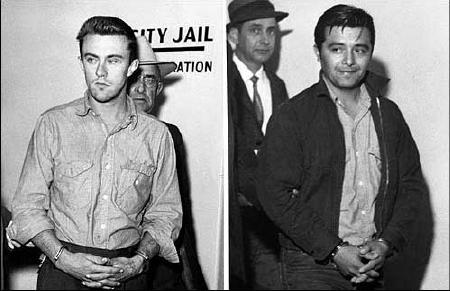

Innocence is guilt!

Innocence is a term that describes the lack of guilt of an individual, with respect for a crime. It can also refer to a state of unknowing, where one's experience is less than that of one's peers, in either a relative view to social peers, or by an absolute comparison to a more common normative scale. In contrast to ignorance, it is generally viewed as a positive term, connoting a blissfully positive view of the world. Over the weekend I watched the early (1967) black and white version of "In Cold Blood" again. In so many ways, it's like revisiting childhood -- not only because I read the book when it first came out (and saw the movie not long after it came out), but because the childish nature of the two psychopaths (Dick Hickcock and Perry Smith) reminds me of a hopeless paradox I've never been able to figure out. I'm not alone in finding this case fascinating. Interest in the Clutter murder case comes and goes in cycles. First there was the book, then the 1967 movie, then a 1996 remake, and now the film "Capote" (which features Perry Smith as a central character). Until today I hadn't known about Perry Smith's central role in "Capote" -- a film which just moved up dramatically on my cinematic priority list. Anyway, this is not a film review, but a childishly unprofessional (hopefully not too psychopathic) review of human nature. Let's start with the premise that Perry Smith was a childish man: The murderer Perry Smith grew up as a physically and psychologically abused child. His parents traveled the rodeo circuit, and his mother became an alcoholic prostitute who died by strangling on her own vomit. His father-the self-styled Lone Wolf-was a fabricator of grandiose dreams and a man of incredible violence. In a quarrel over a biscuit, for example, the father pointed a .22 rifle at his son and said, "Look at me, Perry. I'm the last thing living you're ever gonna see." By mere chance the gun was not loaded. Violent like his father, Perry also inherited from Smith, Sr., the tendency to wish for impossibilities. He dreamed of riches acquired by finding buried treasure in sunken ships, though he could not swim and would not even wear swimming trunks, since his legs and been terribily scarred in a motorcycle accident. Smith also longed to be a nightclub singer, though he had no musical talent or training. Much of his youth had been spent in orphanages and reform schools where he had had to fight his way from childhood to adolescence to manhood. His only reliable companion was a bizarre imaginary friend: a gigantic yellow parrot, in Perry's own words, "taller than Jesus, yellow like a sunflower" that swooped down as a "warrior-angel" and attacked his offenders-as he said, "slaughtered them as they pleaded for mercy" and then gently lifted Perry to Paradise.Here's a picture of the pair right after they were arrested (Smith is on the right):  Perry Smith doesn't seem to have wished the murdered Clutter family any harm, but saw them as people who just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time: About the Clutters, Perry said, "I didn't have anything against them, and they never did anything wrong to me---the way other people have all my life. Maybe they're just the ones who have to pay for it."It's been repeatedly claimed that neither one of these killers would have committed these murders alone, and I'm reminded that the same claim was made about the killers whom Dr. Helen (aka "the instawife") has discussed extensively. (Obviously, not all psychopaths kill, although just as obviously, we worry a lot more about the ones who do.) Smith's childish nature is, I think, also confirmed by his reassuring words to Herb Clutter (head of the Clutter family) in a famous passage from Capote's book: Just before I taped him, Mr. Clutter asked me-and these were his last words-wanted to know how his wife was, if she was all right, and I said she was fine, she was ready to go to sleep, and I told him it wasn't long till morning, and how in the morning somebody would find them, and then all of it, me and Dick and all, would seem like something they had dreamed. I wasn't kidding him. I didn't want to harm the man. I thought he was a very nice gentleman. Soft-spoken. I thought so right up to the moment I cut his throat."He knew the whole time he was going to kill them all, without wishing them any harm. His reassurances remind me of the Nazis telling Jews to be sure to remember where they put their belongings so they could reclaim them after their "showers," and may have been motivated not so out of kindness, but to minimize trouble and help the murders go smoothly. I'm not even sure that when Smith prevented his buddy Hickcock from raping the Clutter girl he was motivated by kindness as much as making things move along according to plan. The disgust he expressed (over "people who can't control themselves") displays impatience with his accomplice rather than empathy for the poor girl, and is more evidence (I think) of an overlapping emotional disconnect shared between psychopaths and children. Probably because of the repugnance factor, many readers will resist thinking of this fiendish killer as a child. But consider the touching spectacle of hardened mass murderer Perry Smith being spoon-fed by the lisping, effeminate Truman Capote: Discovering that Smith is on a hunger strike, Capote buys him baby food and spoon-feeds him back to health. Their relationship is the heart of this movie. Each wants something from the other, and each is willing to reveal a bit of themselves to get it. "You know, we're not so different as you might think," Capote tells Smith as he shares stories from his childhood. As I've said before, I was attacked by children at age two, and I've never since been fully able to understand the claim made that children are innocent, because I know deep down that they are not. At least, the ones who attacked me were not. They attacked without feeling, and without remorse, the way an animal might. (If children are innocent, then why not psychopaths and animals?) I was tied up (so were Perry Smith's victims), and I responded by having an out of body experience. Finally, I was saved by the adults, only to hear them prattle on about which adult had been "responsible." (Something that I'm ashamed to admit made me feel strangely empowered....) But no one considered holding the child perps responsible. No one ever does, and that is because they are "innocent." I knew that the kids were guilty -- far more guilty than any adult (for after all, adults had helped me while they had done just the opposite), but so what? I grew up faster because of it. (At least, so I liked to think....) Anyway, I think this "innocence" is defined by the same feature children share with psychopaths: a total or near total lack of remorse. Of empathy. Of feeling. The absence of a conscience, if you will. If this characteristic is "innocence" in children, why is it considered precisely the opposite -- guilt -- in adults? Actually, I think it may considered a worse thing than guilt. Given a criminal conviction, a defendant's lack of remorse is normally considered an aggravating factor; hence the "cold blooded murderer" is subject to the death penalty, while the hothead who "loses his cool" faces conviction on a lesser charge. In practice, I suppose that means a psychopath who finds his wife in bed with another man, has no strong feelings one way or another, but just shoots him because he feels like killing the guy, why, he's much guiltier than the man who explodes with rage. Temper, temper! Interestingly, the child who loses his temper and misbehaves tends to be dealt with more severely than a child who does the same thing without feeling. It's not my purpose to makes excuses one way or another, whether for children or psychopaths; just to pose a few questions. Is the child's lack of remorse truly a form of innocence, or is it caused by that thing we call innocence? I am not suggesting that a psychopath's lack of remorse should be called innocence; only that it shares similar features, and oddly enough, it may have been formed in childhood. Or it may have not been formed at all. What I mean by that is that the lack of remorse -- something studied by psychologists -- may not be something that psychopaths acquired. Rather, it may be that for whatever reason they never learned to replace innocence with guilt. Instead, they've kept what we'd call "innocence" in a child all the way into their so-called "adulthood." If this is true, if psychopaths are adult children, this in no way diminishes their danger to society (and I'd still pull the lever on 'em), but it does beg a few definitional questions. I hate paradoxes like this, and I'm no closer to the answer now than I was when I was two and thought I'd left my innocence behind. Bad thing, innocence. posted by Eric on 11.14.05 at 04:30 PM

Comments

Wow- fantastic post. Reminds me of bin-Laden's smiling face. Harkonnendog · November 14, 2005 09:05 PM This "innocence," in part, seems to often be a partial detachment from realityŚ psychopaths often describe how other people aren't "real." The inability to accept other people as real? That seems to be very similar to a childhood stage that most people grow out of. "Peek-a-boo" is directly related to a child learning about the permanence of objects (as opposed to out-of-sight, out-of-existence.) Oh yeah. I fully accept the definition of psychopaths as children of a sort. But children grow up, and a child of that sort in an adult body is a perversion. B. Durbin · November 14, 2005 10:35 PM I appreciate the comments. Steven, the Inquisition shrouded itself in a similar air of innocence. Bin Laden radiates calm. I think the innocent type of evil is more ultimately evil than the guilty variety that knows it's bad. Still, there is a difference between believing an evil deed is good and knowing it's evil but not caring. (I'm afraid it won't be resolved in a single post!) Eric Scheie · November 14, 2005 11:19 PM |

|

March 2007

WORLD-WIDE CALENDAR

Search the Site

E-mail

Classics To Go

Archives

March 2007

February 2007 January 2007 December 2006 November 2006 October 2006 September 2006 August 2006 July 2006 June 2006 May 2006 April 2006 March 2006 February 2006 January 2006 December 2005 November 2005 October 2005 September 2005 August 2005 July 2005 June 2005 May 2005 April 2005 March 2005 February 2005 January 2005 December 2004 November 2004 October 2004 September 2004 August 2004 July 2004 June 2004 May 2004 April 2004 March 2004 February 2004 January 2004 December 2003 November 2003 October 2003 September 2003 August 2003 July 2003 June 2003 May 2003 May 2002 See more archives here Old (Blogspot) archives

Recent Entries

• War For Profit

• How trying to prevent genocide becomes genocide • I Have Not Yet Begun To Fight • Wind Boom • Isaiah Washington, victim • Hippie Shirts • A cunning exercise in liberation linguistics? • Sometimes unprincipled demagogues are better than principled activists • PETA agrees -- with me! • The high pitched squeal of small carbon footprints

Links

Site Credits

|

|

In C. S. Lewis's novel Perelandra, the Un-Man (the Devil incarnate) displays exactly that type of "innocence", that utter lack of shame, guilt, or remorse, as he goes about his vile deeds. Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot also never showed the slightest misgivings over what they did to hundreds of millions of their fellow human beings. It was all in the name of "the collective good".